The Network is Unreliable and Reliability is Scary

Indeed the network is unreliable, and this is especially concerning for modern, distributed system. The catch though is that it never can be 100% reliable, and we can't create systems that perfectly compensate for this.

When the Fallacies of Distributed Computing were first written in the 90s, networks were unreliable. The internet was unreliable, intranets were unreliable, even radio was sometimes spotty back then. In the last thirty years, we as an industry have taken this unreliable infrastructure and ... left it there. Packet failures, client timeouts, and the occasional solar flare continue to be a problem not because of any inadequacy on our part but because it's a flaw which is inherent in the system; no network can ever guarantee reliability. Radio is still sometimes spotty because, just like the internet, sending any information over large physical distances is always going to have interruptions and loss. The first Fallacy of Distributed Computing is to assume the opposite of this - the network is reliable - and it's first for a good reason: it really matters.

Now, I wonder if in the last thirty years we haven't actually made this problem worse. In the 90s there weren't a lot of microservice systems making exorbitant use of load balancers, firewalls, gateway APIs, and the like. These are useful tools, but each new component in the distributed stack adds a point of failure. These systems can and do fail in their own right, but the incidence rate of network failures specifically will increase as more of these components are included.

It seems then that we have a good candidate for a first fix: simplify the architecture! Does every microservice need its own firewall? Do we have multiple gateway APIs? A serious and focused audit of the system architecture can reduce a lot of layers in the distributed stack, and overall improve the reliability of the system - the most simple systems tend to be more reliable. However, this only gets us to a certain point - a lot of systems still require load balancing, and you're going to need a firewall somewhere.

Store and Forward (and Retry) #

The simplest implementation to get some fault tolerance is to implement a retry when we see a network error after sending a request. This is store and forward, but I prefer to call it "store/forward/retry" as these all tend to be related. Intermediate systems like gateway APIs and load balancers and the like might have simple implementations of this pattern themselves. To implement this, you'll need to "store" the message, send it ("forward"), and then you can retry on failures as needed by resending the stored message. This pattern works well because it's very simple and provides a good level of recovery from some network errors. It's best practice to implement some sort of retry system - if the packet is dropped en route from client to server, you'll want to be able to resend that.

Idempotency #

There is a problem here though - it is possible for our client to get a network error even if the operation did succeed on the server: suppose the response packet was dropped or the client timed out before receiving the success response. That means that we will potentially send the same request to the server more than once, leading to potential error on the server from reprocessing the same valid, successful request more than once. This is solved by ensuring the operations on the server are idempotent - that replaying the same request twice won't cause these sorts of errors. Indeed, idempotency should be a default for all operations in a distributed system.

Here's a problem on top of that though: some operations cannot be idempotent. I'm currently working in ecommerce, which is rife with examples of single-fire operations: ship an item from an order, send an email when an item was bought from your gift registry, charge a credit card, and so on. In some cases we're able to architect the systems around these to make it so that the web requests are idempotent while the operation isn't. In other cases, we need to be a bit more clever.

Here operation IDs can solve the majority of your problems - generating a UUID for each operation and storing which ones we've processed is a simple solution that works in many cases. That said, non-idempotent operations are sometimes dependent on message ordering in order to work properly. If you're not able to architect away from this, you probably need some more robust patterns. I'll touch on some of these throughout this article.

Boilerplate and Complexity #

There's yet another problem with implementing store-and-forward everywhere - one that affects my day-to-day life much more annoyingly than misordering a customer's packets: now I'll have a bunch of boilerplate around my code! This is a bigger problem for some codebases and less a problem for others. If your application doesn't have a lot of requests and you only need a base level of resilience, then moving the boilerplate into a shared library, or consuming an existing third party library for this, can be sufficient.

On the other hand, if you're setting up a distributed system of even a moderate size, you've probably got a fair amount of traffic going around, and it might make sense to set up a more comprehensive scheme. Some third party libraries do help out here, and allow a sharing of settings across components or provide more intricate solutions for orchestrating some of the request policies across a whole system. Still there are problems here - suppose the client application goes offline before it's able to resend its request, now I might need to add some persistence somewhere if the system requirements need that level of resiliency.

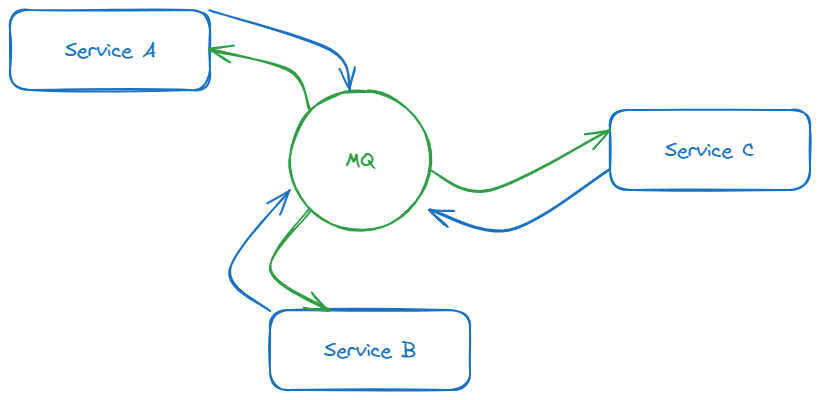

A more powerful alternative to solve this problem is a message queue (MQ). An MQ acts as a standalone message bus for a distributed system, allowing your clients to send their requests into the queue and letting the queue handle all of the considerations to make sure it gets to the client. Most of them offer robust UIs to give you a good level of insight and control over the system, and there are several options that are widely used for this purpose. Now your client needs very little logic in the way of sending a request - it just needs to make sure the request gets to the MQ.

More Complicated Patterns #

The very minimal amount of work that we must do when implementing communication across a distributed system - whether "distribution" in your context means a client and a server or a microservices cluster spanning the globe - is to implement redundancy against the fragile network. In my mind, this means that store/forward/retry and idempotency are the default. As our requirements scale and our systems inevitably become more complicated, these become insufficient either in that they can't satisfy the system requirements or that they don't appropriately guard us against the chaos of the network.

There's another complication on top of this; there's always another complication. Peter Bailis and Kyle Kingsbury, writing for the ACM in 2014 cited some of the only research I am aware of regarding the effects of network fragility on our systems and users. Their work produced this quote (a summary of one such citation), which, to paraphrase what the kids say these days, lives within me without payment of room or board:

Perhaps more concerning is [Microsoft's and the University of Toronto's] finding that network redundancy improves median traffic by only 43%; that is, network redundancy does not eliminate common causes of network failure.

Can we go beyond redundancy and introduce some patterns that will 100% eliminate the effects of network failures? Well, we can introduce some patterns beyond redundancy but we'll never get to 100%.

Asynchronous Communication #

TCP, UDP, and HTTP primarily support request-response type models: I send a request, I wait, and then I get a response. So far we've been considering how this doesn't work, so I think it's natural here to feel that this way of thinking has adopted, at least a little bit, of the fallacy the network is reliable. If I can't rely on getting a response, or even that my request will reach its destination, or if I can't even guarantee that redundancy will be as helpful as I need, then it intuitively follows that relying exclusively on request-response isn't sufficient.

I touched very briefly on the utility of MQs for distributed communication. Indeed, they're a great tool to be able to add a wealth of error handling (and other messaging-related) logic without polluting my codebase(s). I don't think that's the most attractive aspect of these systems though. While most MQs are quite good at supporting a request-response type messaging model, they're exceptional useful if we can move to a fire-and-forget model where I send the request and know I won't get a response.

But wait, my OrderMicroservice needs to be able to get item data from the ItemMicroservice! How do we do this without request-response? The answer in a microservice context is data duplication. The service which is responsible for manipulating the data publishes notifications on changes to that data, and systems which rely on this data will listen to those notifications and maintain their own copies of that data as they need. This is how asynchronous communication works in distributed systems: notify, don't request. This way of thinking changes our system a lot; indeed, it upends our entire architecture. Beyond the change to the communication pattern, it makes data-owning services only singularly responsible for manipulating data, rather than being responsible for both manipulation and querying.

As different as it is from the "traditional" modus operandi, this has almost become the default communication scheme in distributed systems. Particularly systems with varied, geographically distributed components such as IoT and banking (yes, not everything is microservices yet!) It eliminates whole categories of errors, and in our case it helps to eliminate not just one area as a source of network errors (the response) but also supports other best-practice patterns that feed back to helping us maintain our rigidity against the network.

There's tradeoffs though, as there are with all things. Asynchronously communicating systems have trouble reaching consensus, and a lot of times this can be entirely impossible. That's not a dealbreaker for a lot of systems, though it's a major one if your requirements necessitate it.

Outbox #

One common point raised is that as more logic is added around outbound requests, the slower it is to handle those requests. In cases where my hot path is very hot and still needs to produce a fair number of outbound requests (as you might need to if you're notifying on all data change operations), I'll want to optimize my logic as much as I can. Perhaps it will seem attractive to not provide adequate robustness around my requests to make them faster.

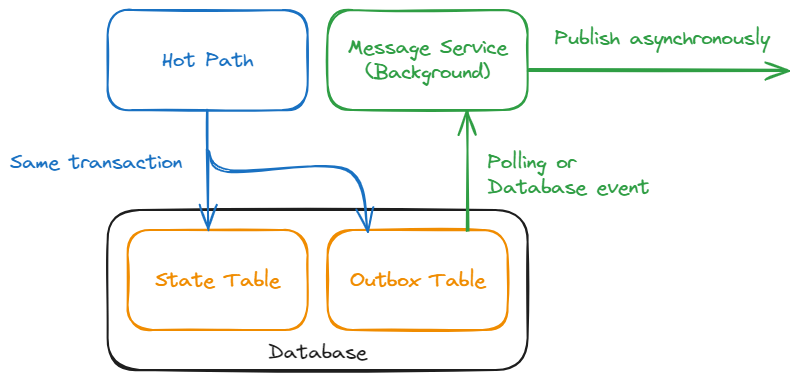

The obvious pattern to use here would be to shuffle your message off to a queue running in a background process that will eventually publish the message, just outside the thread the hotpath is on. This works in a lot of scenarios, but there are robustness concerns yet with this. A helpful pattern here is the Outbox Pattern. The core concept is the same - we maintain a background process in a separate thread which handles sending messgaes with proper resiliency against the faulty network, however the enqueueing mechanism is the clever bit.

This pattern suggests that your database should have a table, or tables, containing the messages which you want to enqueue - this is the "outbox" table. When your application makes the update to the business objects in the database, in the same transaction it would add the message to be sent to the outbox table. The background message sending process then listens to this table (either by polling or by having the database raise events) to perform the sends. This is clever because, while you do need to write the logic to insert the message into the table, you don't specifically need to call the message publishing service to enqueue the message. On top of this, that you're using your database as the queue gets you a persisted queue for free.

This pattern is worthwhile if you've got a hot hot path, need the extra resiliency in your queue, and the extra cost of running the background process is worth it to you.

Event Sourcing #

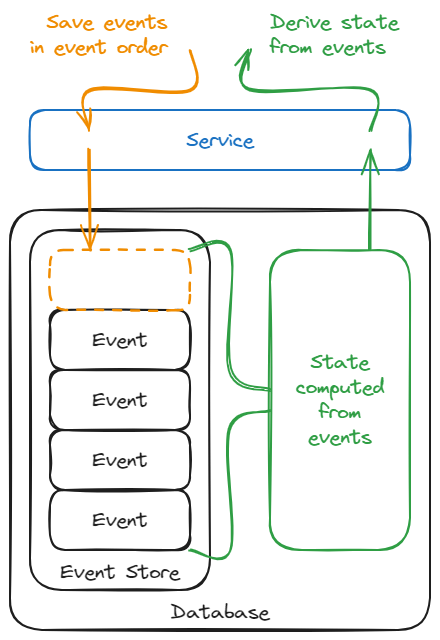

Some applications have a high need to preserve message ordering, usually because the state of the system is dependent on the temporal changes over the course of several events. These systems are good candidates for event sourcing, and this pattern can help us alleviate some of the pain of hardening our system against a faulty network.

This pattern imposes (very broadly) that you should save all of the events which alter your state, and that the state should subsequently be derived from these events. This is opposed to our traditional way of persisting data, where we process an event, update the state to reflect the changes specified by that event, and then forget the event. Event sourcing allows a number of benefits like being able to replay state, but what's interesting to us is that it allows inserting an event in the middle of a set of events which have already been processed.

This is beneficial to us if message ordering is high on our considerations list. If we're implementing proper resiliency when messages are dropped on the wire, we're going to be retrying messages, and there's a fair chance we're going to be sending some messages out of order in this scenario. As long as our events are properly dated, they can be ordered appropriately (and change the state appropriately) in our eventually-consistent system. This pattern also has the power to transform some non-idempotent operations into idempotent ones - instead of changing the state directly in a non-idempotent way, we'd be inserting/upserting/updating the single event in an idempotent way.

One word of warning though - event sourcing is a huge pain to implement and maintain. This pattern can very quickly get very complicated, and if you're careless then you can mangle data over time. Systems like EventStoreDB or the postgresql-event-sourcing plugin can help to make this easier, but that of course requires an investment in those systems. This is a pattern to study carefully and only use if it's appropriate for your use case.

Chosing the Right Solution #

The trend which I think is plainly obvious here is that each next step we take in the battle against the unreliability of the network introduces greater and greater rippling effects across our code, infrastructure, and architecture. It's common advice for most any problem in distributed computing - not just this one - that the best solution is for us to upend just about everything we know about software engineering! Okay, I'm being a bit facetious, but as solid and well-proven as patterns like asynchronous communication are, they're quite different to other ways of writing software.

Difference between domains isn't bad in itself. A CRUD API is never going to look anything like a desktop application, which is going to look entirely different itself from any video game code you might find. It's probably a sign of being on the right path that we find that radically different domains produce radically different styles of engineering and architecture. Distributed systems aren't a single, contiguous domain though: the architecture we consider for a client-server system is itself going to be radically different from a microservices cluster, and yet they're both "distributed". Some patterns are going to work better or worse depending on the requirements of each different system.

Cost-Benefit #

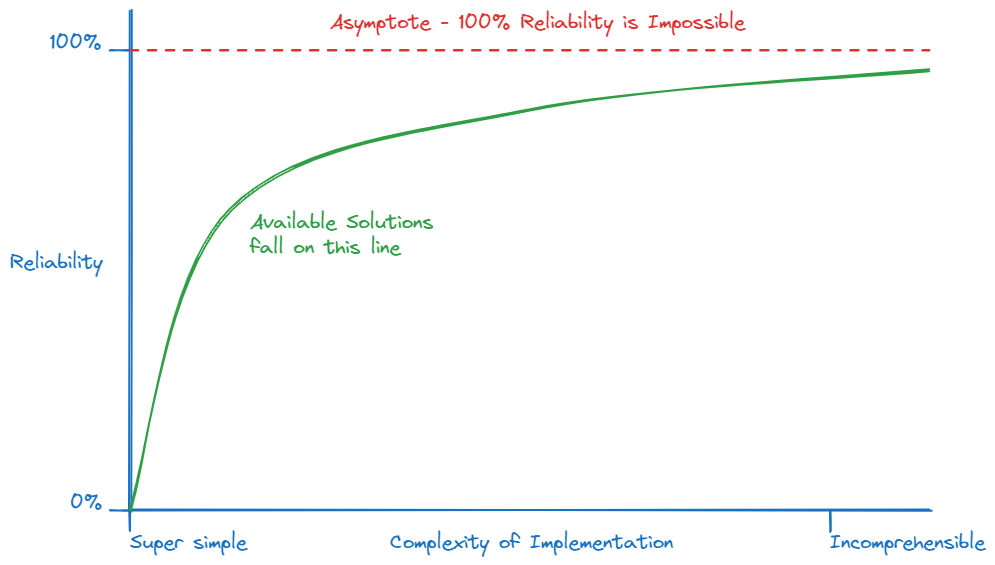

Extending the observation that the increasing steps exacerbate the complexity of our systems, we can say that the more reliable of a system you engineer, the more costly it is. I have no evidence for this, but it is maybe helpful to assume a sort of exponential or logarithmic growth in cost vs. reliability (I know "exponential" and "logarithmic" are very different but I slept through math class, passed by answering "C" on all the questions, and for my purposes they occupy the same category in my brain, right next to Snoopy and Woodstock). 100% reliability can never be achieved, so there is some point of reliability which becomes cost ineffective for your firm.

I don't have an answer for this. I can bring up patterns with a pros and cons list all day - I've presented a couple here - but this comes down to a study by your team and firm for its use case. Start by engineering a redundant system and extend (or replace) the components and architecture where you need. Since we can't ever achieve 100% reliability, we'll need to throw in the rag at some point and accept that failure has to be an option, but remember that failure is only an option if we've explicitly coded for it.

How Do We Know Our Solutions Work? #

How do we know we've engineered a system which is appropriately reliable given our domain? Here's one more quote from that ACM paper:

Moreover, in this article, we have presented failure scenarios; we acknowledge it is much more difficult to demonstrate that network failures have not occurred!

Indeed, you can't prove that something didn't happen. With appropriate monitoring you can get an insight into how frequently network failures tend to occur, and you should track these and line them up with any cascading system failures. Generally, the absence of these indicators suggests strongly enough that there are no failures occurring.

Using this data to feed back to know if you've over- or under-engineered your system is a different beast, though. This is part of the art of our field. Especially with the patterns we're talking about here, it's almost impossible to do A/B testing. I recommend a gradual approach: start with the lowest amount that you need, and if your monitoring indicates failures in a particular way, then address those in the minimally-invasive way and repeat.

Conclusion #

The network is unreliable and it won't ever be reliable. I've presented some of the general patterns to consider here, but there's a wealth of ideas on this topic. The job of creating properly resilient systems is about balancing tradeoffs as your requirements demand. There are dozens of patterns out there for dealing with this problem in different domains, trading off one bit of reliability for performance or one style of communication for redundancy, or any other tradeoff you might make.

Like the approach to the other fallacies, the right approach to this one (insofar as there is any "right" approach) is one of mindset more than code. The fallacies are so-named not because they're actual logical fallacies but because the point is to remind us it's a mindset problem. If we engineer our systems from the mindset that the network is reliable, then we'll end up with a deficient system because it's not true. If we adopt the proper mindset that not only is the network unreliable but also that it's a difficult and domain-specific problem to solve, we'll end up engineering thoughtful and considered systems.