Book Club 12/2024: Team Metrics and KPIs

Allow neither ignorange nor complacency to abuse metrics or KPIs; these are important tools for the competent professional.

Happy holiday season and new year to you all! In the week between the holidays here I'm thinking about metrics and KPIs and the whatnot that we use in our team processes. Are they useful? My typical answer for any such question on this blog: yes of course, if they're being used well for a particular situation and so on and so forth. Measuring things can be good or bad.

Is there a feeling that metrics are largely useless? I don't know. There's plenty of opinions to be found on good and bad metrics, and good and bad use of metrics. I don't have a lot of patience to entertain a whole host of disparate, two-bit opinions, so I might suggest cutting through everything by asking: Are the metrics measuring something of value which are used to address a specific problem, and is the whole deal well-defined?

Most scrum teams measuring velocity are doing so out of habit, and that's probably useless (this is where the term "cargo cult" is often misapplied in blog posts like these), but other teams might have noticed some issue in their process and solved it by measuring a KPI. Specific measurement, specific problem, specific definition. The KPI for KPIs seems to be degree of specificity. Are meta-KPIs a thing? I did a Google search after writing that last question and can happily report that they are not a thing.

I've got a couple stories about metrics then, one bad and one good.

The bad one relates to code coverage. This, like velocity, is one of the typically useless metrics. Not because of some inherent uselessness, but it happens more often than not that they're misused in some way, typically they're there just for the sake of it. But my story about code coverage:

I now test all of my distributed services almost exclusively via integration testing of some sort. All the code of the service is a black box to the tests, which are able to cover all of the business and technical cases the service might fall into. I use Gherkin so that the tests are readable to all stakeholders, which allows a BDD process that greatly simplifies the process of quality assurance.

Is a code coverage metric useful here? Unequivocally, no. What would be useful here is some way to measure what percentage of the business cases the tests cover. That's probably not achievable, but code coverage is useless. If I have written tests to prove that the service satisfies all of the business cases, the code itself is quite beside the point. Indeed, these services end up with very a very high degree of code coverage, but that metric gives me nothing of value except the percent of code not contributing to satisfy the business constraints. Maybe I have added some code to output to a non-critical or temporary admin report. Maybe I'm testing a new feature, or any host of things. Even having code coverage suggests the code doesn't mean to be there. Even worse, the build gates on the repositories for these services have coverage requirements. That's even more useless - now I can't check in these extra bits of code without some manual exclusion from the coverage report! Alas, there's an organizational momentum behind the damned thing and there's only so many demons you can stomp on at once.

My second metrics story is, on the other hand, a story about a good use of metrics. Many years ago (how time flies, it feels like it was yesterday) I was leading a team developing a new SaaS product, and we noticed that work would go through periods of stagnation owing to PRs being open too long, and once several of them accrue bad things tend to happen. Indeed we discussed whether we needing a PR process and decided that we did want it, so we sought to address the issue by measuring PR open time and asking five whys to find all the root causes of this stagnation.

I crafted a spreadsheet as a sort of dashboard to show open PRs, their state, how long they've been open, and the like. I was able to regularly touch base with PR authors and reviewers when we noticed some slippage. I mean this to be a success story about a metric, but I figure the real star here is the "five whys" method (or, perhaps, any method to get deeper than the surface level of a problem) because indeed the real causes of stagnation were varied and not all what you'd have expected. I suppose then the success of the metric is it allowed those conversations to happen efficiently.

At any rate, in very short order we had addressed a number of underlying issues with the development process, and after just a couple of months we settled into a pace and process that allowed a phenomenal amount of code to be written over quite a bit of time. Great success!

I don't write on metrics or KPIs, but I do write a fair bit about process. Here's my reading/watching from the past month:

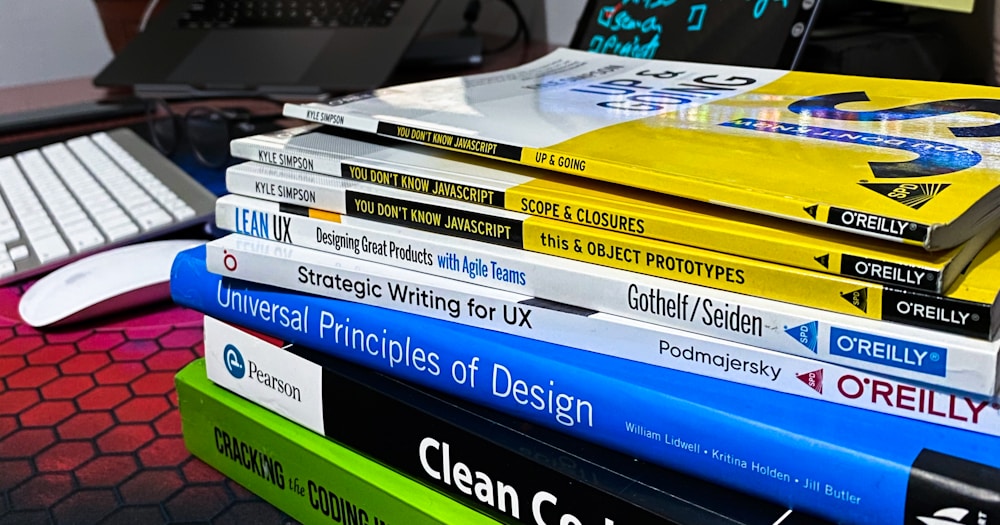

Reading

- Useful engineering metrics and why velocity is not one of them - Lucas F. Costa

- The Luxury of Working Without Metrics - DHH

- Bug Tracking for Agile Teams - Gojko Adzic

- On productivity metrics and management consultants - Lorin Hochstein

- TTR: the out-of-control metric - Lorin Hochstein

- Practical Ways To Increase Product Velocity - Stay SaaSy

- Several posts on metrics by Martin Fowler

Listening

Watching

- The BEST Developer Productivity Metrics We Have... SO FAR" - Dave Farley and Martin Fowler

- How to Measure Success for Development Teams - Dave Farley

- Software Development in the 21st Century - Martin Fowler

- Why KPIs and Metrics Should Not Become Targets - Bernard Marr

- Measuring Software Developer Productivity??? - ThePrimeagen